A Cartoonist Transforms into Diverse Superhero

June 13, 2018

Facing Hate and Discrimination While Wearing a Dastaar

August 2, 2018Years ago, when far fewer conversations were taking place around the need for diverse books, I took the necessary leap to launch a small independent children’s press in Canada. I could not have predicted then, that our first title – A Lion’s Mane – would go on to win an Honor Book Award for Multicultural and International Awareness.

For almost a decade before then, manuscript submissions had swept back under my door. Despite the emotional toll of rejections from traditional publishers and then, reviewers for A Lion’s Mane remarking, “your community doesn’t buy books”, or “your stories are probably better suited to your own community”, I am thankful that those privileged voices did not distract me. My community did (and does) read. You would be hard-pressed to not find a variety of newspapers, novels, poetry books and oral storytellers in the homes of the south-Asian community I lived amidst. Those remarks did not reflect my reality.

[Image Credit: Baljinder Kaur]

Literary experiences from my youth had rooted a false narrative into my psyche – that our stories must be less important, or that we needed to conform to stereotypes to have spaces in books. I was an avid reader, but usually ended up in the adult section at the Library, to find historical fiction relating to monuments like the Taj Mahal or titles like “All About Sikhs” to find any representation. Categories like Food and Festivals were always on hand, of course, but it was as if our lives held no intersectionality.

As a classroom teacher though, I saw groups of children open up to learning something new, every single day. They were open to asking questions. And then life happened, and I became Mum to a child with profound hearing loss. I knew it was time. It was necessary now. Saffron Press would reflect the Sikh identity in children’s literature, without propelling (subtle), colonially ingrained or even culturally enforced stereotypes.

[Image from The Garden of Peace; Illustrated by Nana Sakata]

[Image from The Garden of Peace; Illustrated by Nana Sakata]

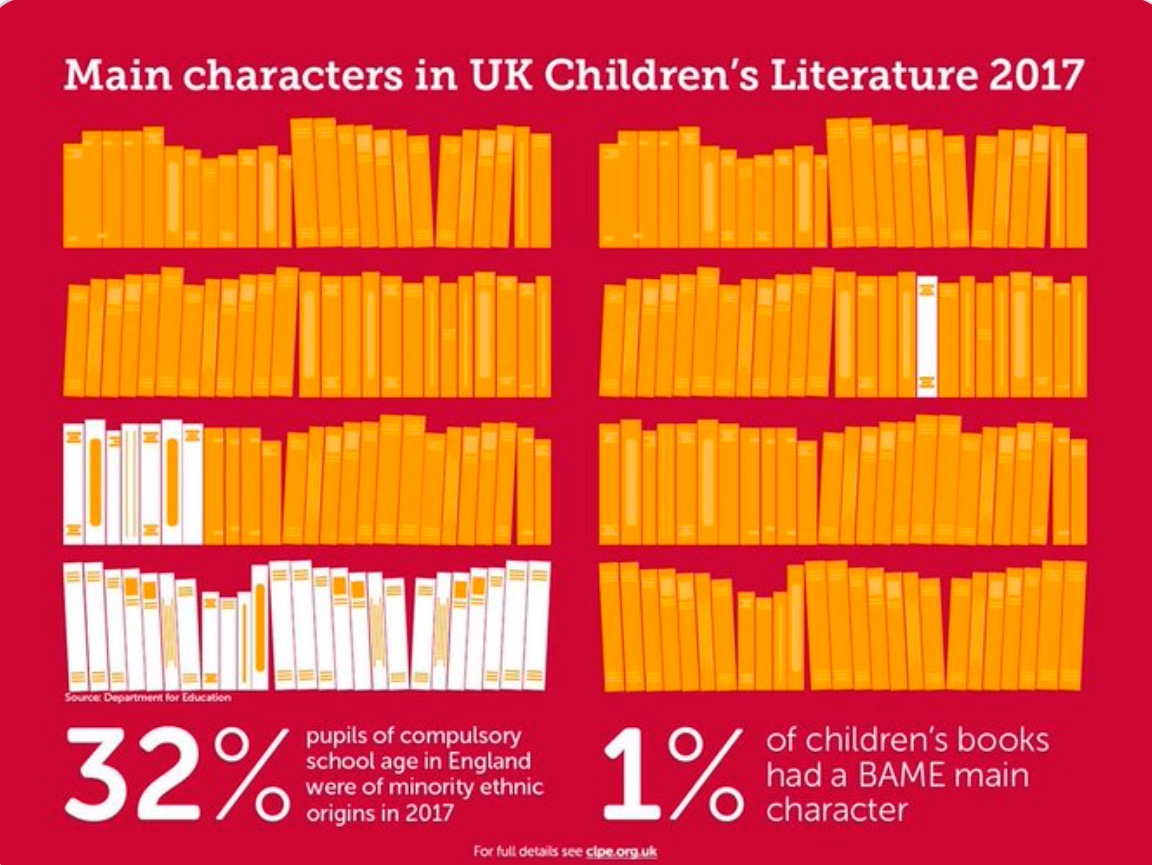

With recent media attention from a study by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), to gather data about BAME (Black Asian and Minority Ethnic) characters in children’s books published in the U.K. in 2017, the results reveal that not much has changed since my own childhood growing up in the North of England.

Publishing ‘diverse’ books is not enough to change mindsets when it comes to collecting data around how many times a book is checked out of the library, for example. Whose stories are stocked on library or classroom shelves in the first place? Who decides which books are placed face out and distributed? Are the means and margins even accessible to smaller presses or independents? Is it equitable to demand the same trade discount from small independents as traditional publishers with print runs in the thousands of copies? Is it sustainable for small presses and independents to remain competitive in this industry? Absolutely not, and that’s where power and privilege come in to play.

While reading conversations across social media since the CLPE study, I’ve been acutely aware of an underlying tone of the word tolerance – nobody should tolerate diverse characters – it’s not about tolerance, it’s about humanizing stories with diverse lives and experiences and, accepting that difference and bias exist.

Authors of colour who have chosen to self-publish their work know first-hand that the reins of power exist, but we also know what happens when silence remains. By examining power and privilege, people in the industry can decide whether their privilege can be used to elevate those facing inequity. Who is writing the stories with BAME characters? Are the representations even accurate? The CLPE study highlights necessary conversations and I hope it will help break down long-standing barriers in the industry.

Small presses and independent authors advocate fiercely to share space at any table. Without the support of readers invested in buying and sharing more diverse books, and local indie bookstores giving space to social justice issues on their shelves, the obstacles are insurmountable. Community can change the landscape of where diverse books are found and by whom.

So, while the gathering of data is significant – after all, we need data to drive change – it is essential to reflect on the data through a critical lens. As a woman of south-Asian heritage running a small independent press, I can speak from a place of knowledge. I appreciate the pressures of saleability and getting starred reviews or awards but the idea of why we need diverse books is much larger – it’s about normalizing marginalized experiences so that the children of IBPOC2+ do not see books with only White characters on the front covers.

Researching diverse children’s literature and sharing that truth with a population is one step along a very long journey. (In Canada, we are not even there yet). Dismantling the power that exists around every corner of the journey is considerably harder.

I have said this before but I’ll say it again, every time you choose a book to read or share, you are making a political choice. A choice between whether you are comfortable with the status quo, or if you are ready to stand for change. I hope you will choose the latter and support indie authors and presses. I hope you will look for #OwnVoice stories and accurate representation, because we are the groundswell, and we need you to be part of that wave.

[Image from The Garden of Peace; Illustrated by Nana Sakata]

[Image from The Garden of Peace; Illustrated by Nana Sakata]

1 Comment

[…] all white) publishing team very well and I wasn’t sure if they were on the alert regarding the diversity gap in publishing, so I hired a trained fact-checker from Texas Monthly magazine to go through all of the topics I […]